Tuples filter on multi columns with Django ORM

Introduction

As a daily Django user, I often encounter the need to filter on multiple columns with a tuple of values. For a long time, there was no built-in support in Django ORM for this use case, and developers had to come up with workarounds to achieve the desired result.

In this post, I will discuss some common workarounds, then present a solution that was “shadow” released together with Django 5.2, but has not been made public yet.

I will also dedicate a section to run some benchmarks (with code) to compare the performance of the different solutions using a PostgreSQL database.

Problem statement

Let’s take a simple example to better illustrate the use case, given the following model:

1

2

3

4

class People(models.Model):

first_name = models.CharField(max_length=255)

last_name = models.CharField(max_length=255)

age = models.IntegerField()

We want to calculate the average age of some people from the table, based on an input list of first and last names. Ideally, the raw query should look like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

SELECT AVG(age) FROM people

WHERE (first_name, last_name) IN (

('John', 'Doe'),

('Jane', 'Doe'),

...,

('John', 'Smith')

);

Solutions

1. Build the filter conditions manually

This is the most common workaround, using the Q object to generate the filter conditions.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

from django.db.models import Q

filter_conditions = Q()

for first_name, last_name in input_names:

filter_conditions |= Q(first_name=first_name, last_name=last_name)

queryset = People.objects.filter(filter_conditions)

average_age = queryset.aggregate(Avg('age'))['age__avg']

Which will generate the following SQL query:

1

2

3

4

5

6

SELECT AVG(age) FROM people

WHERE (first_name = 'John' AND last_name = 'Doe')

OR (first_name = 'Jane' AND last_name = 'Doe')

OR ...

OR (first_name = 'John' AND last_name = 'Smith')

;

At first glance, some (myself included) might assume that this is quite different from the desired query, and the performance might be worse.

However, for PostgreSQL engine, the IN clause is translated to a WHERE clause with multiple OR conditions, so our generated SQL query is actually closer to what will be executed by the database engine.

Even though this solution is valid on the database level, it still has some drawbacks:

- Additional code to generate the

Qobject and harder to extend, for example when there are more than two columns to filter on. - The generation of the

Qobject will consume more memory and time on the Python side. In most cases, this is negligible, but it might become significant when the input list is much larger. - The generated SQL query is larger, and will take longer to send to the database.

2. Custom Tuple function

This workaround involves creating a custom function that will generate the tuple field via an alias, then use it in the filter method with normal in lookup.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

from django.db.models import Func, Value

def ValueTuple(items: list[tuple]):

return tuple(Value(i) for i in items)

class Tuple(Func):

function = ""

queryset = (

People.objects

.alias(a=Tuple("first_name", "last_name"))

.filter(a__in=ValueTuple(input_names)

)

The generated SQL query should be identical to the desired query. However, in addition to the same drawbacks as the previous solution, another issue is that it only works with psycopg2 (not psycopg3 due to this change), which is no longer in active development.

All other flavors of this workaround (such as RawSQL) also share the same problems, so I won’t cover them here.

3. Hidden feature in Django 5.2

Django 5.2 was released recently and introduced the long-awaited support for Composite Primary Keys. A new internal module was added as part of this feature, django.db.models.fields.tuple_lookups, which includes built-in support for tuples with IN lookup.

Be aware that this internal module has not been made public in the Django API or documentation yet. This means that it might not be stable and is subject to change in future versions of Django, so use it at your own risk.

The usage is straightforward:

1

2

3

from django.db.models.fields.tuple_lookups import Tuple, TupleIn

queryset = People.objects.filter(TupleIn(Tuple("first_name", "last_name"), input_names))

The generated SQL query should be identical to the desired query.

To bench or not to bench

At this point, the first question that comes to mind is which solution should we use? Naturally, we would want the best performing solution. However, all solutions generate the same or equivalent SQL query, so theoretically the performance should be roughly identical. In real-world scenarios, would we see any difference?

The only way to know is to run some benchmarks.

If you are interested in the making process of the benchmark, please continue reading. Be aware, the following section is very code-heavy.

Otherwise, you can skip directly to the Benchmark results.

Benchmark preparations

Environment configurations

For reference, here are the details of the environment used for the benchmark:

- OS:

debianon WSL2 on Windows 11, limited to 4 CPU cores and 8GB of RAM - PostgreSQL 15: installed directly into the WSL2 instance instead of using Docker container

- Django 5.2: required for solution 3

- psycopg3: driver interface for PostgreSQL

- Python 3.13: because why not?

The configurations don’t really matter as long as we are running the same tests on the exact same environment.

Generate test models

The base model to be tested will be the following:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

from django.db import models

class ExperimentBase(models.Model):

first_name = models.CharField(max_length=255, db_index=True)

last_name = models.CharField(max_length=255, db_index=True)

age = models.IntegerField(db_index=True)

email = models.EmailField(max_length=255, null=True, blank=True)

created_at = models.DateTimeField(auto_now_add=True)

class Meta:

indexes = [

models.Index(fields=["first_name", "last_name"], name="%(class)s_name_index"),

]

abstract = True

# Must be set by subclass

_max_count = -1

@classmethod

def submodels_by_size(cls) -> dict[str, type["ExperimentBase"]]:

submodels = {}

for submodel in cls.__subclasses__():

if submodel._max_count == -1:

continue

key = f"{submodel._max_count // 1_000_000}M"

submodels[key] = submodel

return submodels

@classmethod

def experiment_methods(cls) -> list[Callable]:

return [

cls.filter_rows_with_in_tuples,

cls.filter_rows_with_conditions,

]

@classmethod

def filter_rows_with_conditions(cls, inputs: list[tuple], input_columns: list[str]) -> float:

conditions = Q()

for input_tuple in inputs:

conditions |= Q(**dict(zip(input_columns, input_tuple, strict=True)))

query = cls.objects.filter(conditions)

return query.aggregate(Avg("age"))["age__avg"]

@classmethod

def filter_rows_with_in_tuples(cls, inputs: list[tuple], input_columns: list[str]) -> float:

query = cls.objects.filter(TupleIn(Tuple(*input_columns), inputs))

return query.aggregate(Avg("age"))["age__avg"]

The columns’ indexes are varied to simulate different scenarios.

The _max_count class variable is used to determine the number of rows to generate on each submodel, while the submodels_by_size method returns a dictionary of all submodels by their maximum number of rows, which will simplify the experiment code later on.

Only solution 1 (method filter_rows_with_conditions) and solution 3 (method filter_rows_with_in_tuples) will be tested, since solution 2 generates the same query as solution 3.

Generate dummy data

We will have to create a distinct table with each required number of rows, which is trivial by subclassing the base model above:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

class Experiment5M(ExperimentBase):

_max_count = 5_000_000

class Experiment10M(ExperimentBase):

_max_count = 10_000_000

class Experiment20M(ExperimentBase):

_max_count = 20_000_000

Needless to say, the makemigrations and migrate commands will be necessary to create the tables in the database.

To generate dummy data, we will use the Faker library:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

from faker import Faker

class ExperimentBase(models.Model):

...

@classmethod

def bulk_generate_rows(cls, bulk_size: int = 10_000) -> None:

current_count = cls.objects.count()

number_to_create = cls._max_count - current_count

fake = Faker()

while number_to_create > 0:

bulk_size = min(number_to_create, bulk_size)

cls.objects.bulk_create(

[

cls(

first_name=fake.first_name(),

last_name=fake.last_name(),

age=fake.random_int(min=18, max=90),

email=fake.email(),

)

for _ in range(bulk_size)

]

)

number_to_create -= bulk_size

logger.info(f"Number to create remaining: {number_to_create}")

The bulk_generate_rows method will generate rows until the table reaches its maximum number of rows.

To execute the generation, we will use a simple management command that will loop through all the submodels and call the bulk_generate_rows method.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

# experiments/management/commands/generate_rows.py

from django.core.management.base import BaseCommand

from experiments.models import DEFAULT_BULK_SIZE, ExperimentBase

class Command(BaseCommand):

help = "Generate rows. Example: python manage.py generate_rows --bulk-size 100000"

def add_arguments(self, parser):

parser.add_argument("--bulk-size", type=int, default=10_000)

def handle(self, *args, **options):

bulk_size = options.get("bulk_size")

for experiment_table in ExperimentBase.submodels_by_size().values():

experiment_table.bulk_generate_rows(bulk_size=bulk_size)

This implementation allows interrupting and resuming the generation at any time, which is useful since the process will take quite a while to complete (around 10 minutes for 5 million rows on my machine).

It is possible to “cheat” the process by using pure SQL to duplicate the table from an existing one, for example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

INSERT INTO experiments_experiment10m (first_name, last_name, age, email, created_at)

SELECT first_name,

last_name,

age,

email,

'2025-04-30 00:00:00+00'

FROM experiments_experiment5m;

Generate list of input tuples

PostgreSQL uses an internal caching mechanism (shared buffers) for each query, which means the same query inputs will be much faster on subsequent runs.

To minimize the impact of this mechanism on the results, we will have to generate a new list of input tuples for each test / run.

Additionally, to simulate real-world scenarios, we will generate a ratio of 90% real inputs (existing data from the table) and 10% fake inputs. The real inputs will be selected from a random range of the table, and the fake inputs will be generated randomly with Faker.

The following method will generate input tuples for first_name and last_name columns:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

class ExperimentBase(models.Model):

...

@classmethod

def generate_inputs(cls, number_of_inputs: int, fake_percent: int = 10) -> list[tuple[str, str]]:

# Generate fake inputs

columns = ["first_name", "last_name"]

number_fake_inputs = int(number_of_inputs * fake_percent / 100)

fake = Faker()

fake_inputs = [(fake.first_name(), fake.last_name()) for _ in range(number_fake_inputs)]

# Get inputs from the database with random offset

number_real_inputs = number_of_inputs - number_fake_inputs

random_index = random.randint(0, cls._max_count - number_real_inputs)

real_inputs = cls.objects.values_list(*columns)[random_index : random_index + number_real_inputs]

return list(real_inputs) + list(fake_inputs)

Full implementation of the ExperimentBase class can be found here.

Command to run the experiments

The last step is to run the experiments with a management command:

flowchart LR

A(Loop through experiment methods) --> C(Loop through submodels)

C --> E[Generate inputs with required tuples and columns]

E --> F[Call experiment method]

F --> G[Measure average duration]

G --> C

Benchmark results

Test scenarios

We will run the experiments with the following variables:

- Number of runs for each scenario: 200

- Number of fake inputs: 10%

- Number of rows in the table: 5 / 10 / 20 / 50 million

- Number of columns to filter on: 2 / 3 / 4

- Number of input tuples: 100 / 200 / 500 / 1000

Each following section will show the results for a specific input size (100 / 200 / 500 / 1000 tuples).

Some notes to keep in mind to interpret the results:

- Method 1 will be referred to as “Conditions”

- Method 3 will be referred to as “Tuples”

- Average runtime values are measured in milliseconds (ms). Lower values indicate better performance.

- Green indicates better performance. Red indicates worse performance for the corresponding vertical category.

- Percentage difference is calculated as:

(conditions - tuples) / tuples * 100% - Positive indicates

Tuplesis faster, Negative indicatesConditionsis faster

Without further ado, let’s dive into the results!

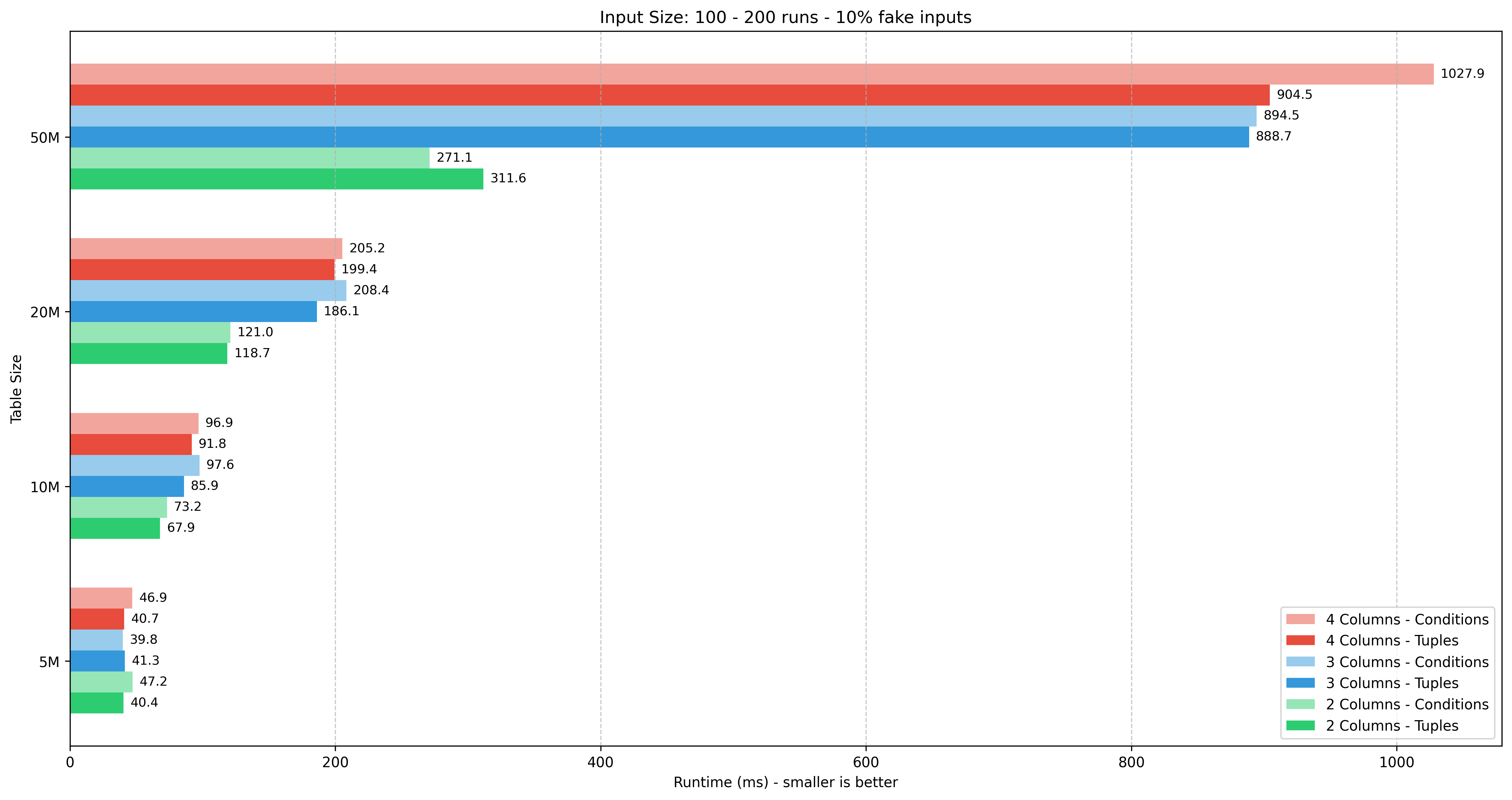

Input size: 100 tuples

| Table size | 5M | 10M | 20M | 50M | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Columns | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||

| Tuples | 40.37 | 41.27 | 40.74 | 67.86 | 85.86 | 91.80 | 118.68 | 186.11 | 199.40 | 311.60 | 888.73 | 904.46 | ||||

| Conditions | 47.17 | 39.84 | 46.88 | 73.25 | 97.60 | 96.88 | 120.98 | 208.38 | 205.20 | 271.15 | 894.51 | 1027.91 | ||||

| Diff % | +16.8% | -3.5% | +15.1% | +7.9% | +13.7% | +5.5% | +1.9% | +12.0% | +2.9% | -13.0% | +0.6% | +13.6% |

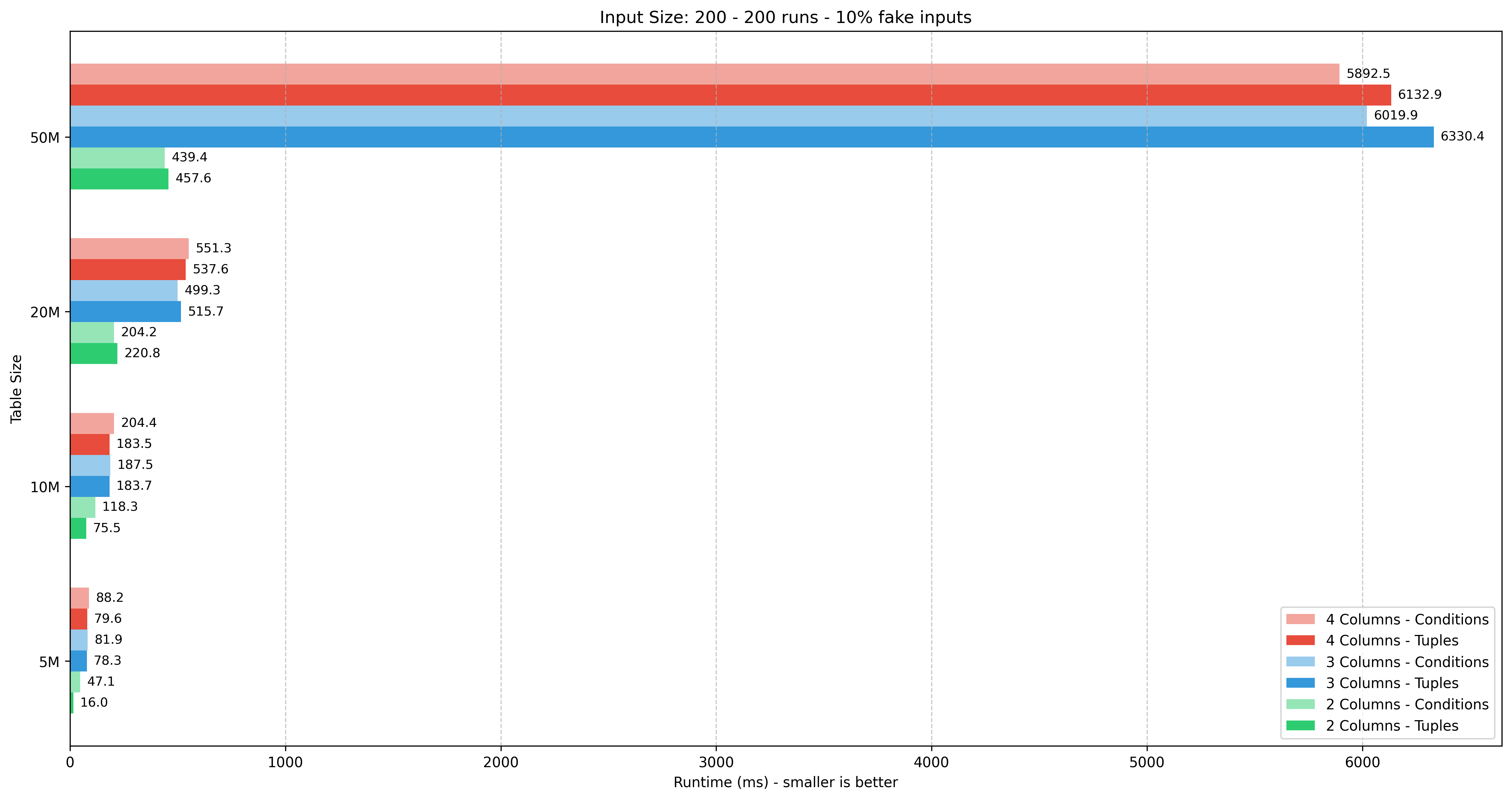

Input size: 200 tuples

| Table size | 5M | 10M | 20M | 50M | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Columns | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||

| Tuples | 16.00 | 78.35 | 79.60 | 75.47 | 183.72 | 183.50 | 220.84 | 515.70 | 537.60 | 457.63 | 6330.45 | 6132.87 | ||||

| Conditions | 47.09 | 81.92 | 88.23 | 118.30 | 187.51 | 204.45 | 204.22 | 499.34 | 551.31 | 439.38 | 6019.89 | 5892.50 | ||||

| Diff % | +194.3% | +4.6% | +10.8% | +56.8% | +2.1% | +11.4% | -7.5% | -3.2% | +2.6% | -4.0% | -4.9% | -3.9% |

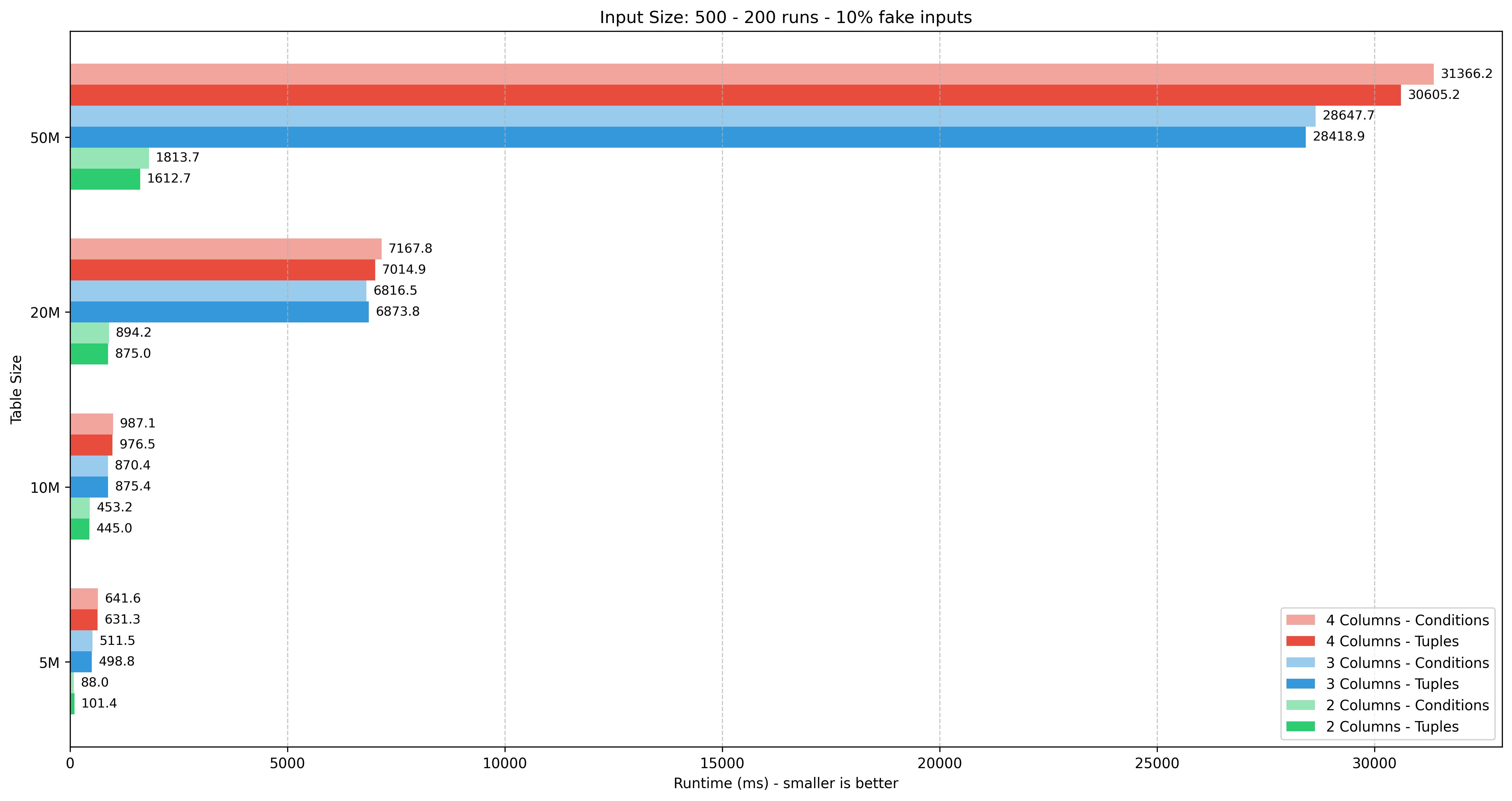

Input size: 500 tuples

| Table size | 5M | 10M | 20M | 50M | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Columns | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||

| Tuples | 101.41 | 498.82 | 631.32 | 445.00 | 875.42 | 976.52 | 874.98 | 6873.76 | 7014.91 | 1612.65 | 28418.94 | 30605.16 | ||||

| Conditions | 88.00 | 511.50 | 641.60 | 453.16 | 870.41 | 987.06 | 894.18 | 6816.49 | 7167.83 | 1813.69 | 28647.71 | 31366.24 | ||||

| Diff % | -13.2% | +2.5% | +1.6% | +1.8% | -0.6% | +1.1% | +2.2% | -0.8% | +2.2% | +12.5% | +0.8% | +2.5% |

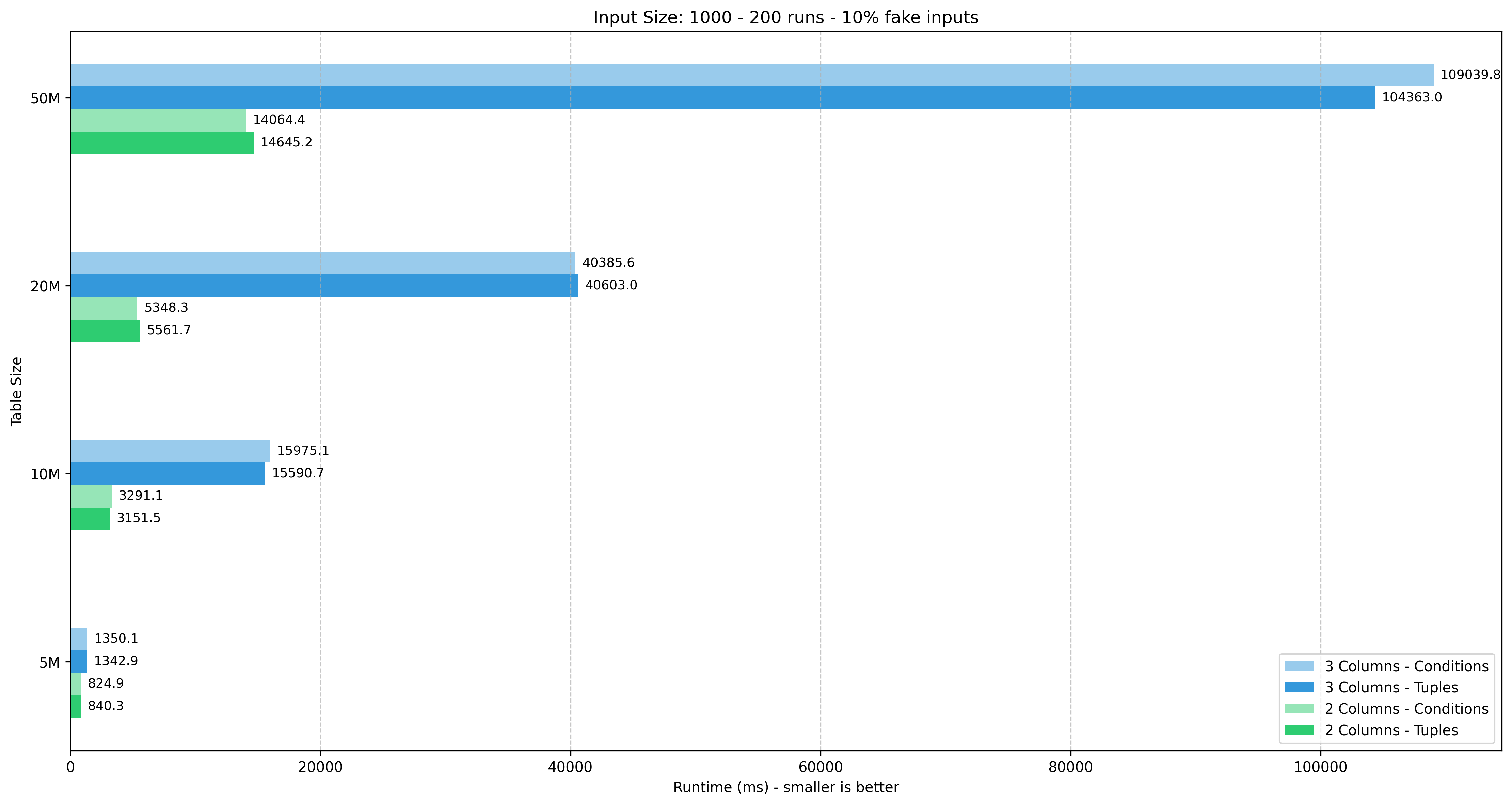

Input size: 1000 tuples

| Table size | 5M | 10M | 20M | 50M | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Columns | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||

| Tuples | 840.32 | 1342.87 | TBD | 3151.48 | 15590.67 | TBD | 5561.74 | 40603.01 | TBD | 14645.16 | 104363.03 | TBD | ||||

| Conditions | 824.89 | 1350.06 | TBD | 3291.13 | 15975.14 | TBD | 5348.29 | 40385.59 | TBD | 14064.40 | 109039.78 | TBD | ||||

| Diff % | -1.8% | +0.5% | TBD | +4.4% | +2.5% | TBD | -3.8% | -0.5% | TBD | -4.0% | +4.5% | TBD |

I had to abort the experiments for 1000 tuples on 4 columns, because it was taking too long to complete at this point (24 hours!).

Observations

- Tuples wins in 30/44 test scenarios

- The performance difference is quite minimal, within

5%for 30/44 scenarios. However, there were some big anomalies, for example in 200 tuples test cases. - The input size has a big impact on the performance. In the worst case scenario (50M rows), the difference between 100 vs. 200 / 500 / 1000 tuples is 6x / 30x / 100x respectively.

- The additional column has a much bigger impact on performance for larger tables, from 10M rows and above. The lack of composite index in 3 and 4 columns might also play a role here.

Conclusion

Even though the performance difference is pretty minimal, it is pretty safe to say that the Tuples method is the clear winner here. This difference could be explained by the fact that the resulting query is smaller with the Tuples method, thus is faster to transfer to the database server for execution.

Besides better performance, the Tuples method has become a built-in feature in Django 5.2, which renders the code much cleaner and easier to maintain. However, it is still not recommended to use it in production, as the feature hasn’t been officially released, and there might be some edge cases that are not yet covered.

The experiment might not be perfect, but I do enjoy the process of building the benchmark and testing various theories I have in mind about Django ORM and PostgreSQL. It took me a whole day to complete almost all the test scenarios, which was not wasted time since it allowed me to plot the graphs and finish writing this very post.

I hope this post helps you make an informed decision on which method to use, and I hope you enjoyed reading as much as I enjoyed writing it.

The whole code for the experiment is available on GitHub.